In occasione della mostra personale “Anj Smith. A Willow Grows Aslant The Brook” dedicata all’artista Anj Smith e curata da Sergio Risaliti al Museo Stefano Bardini di Firenze, la pittrice racconta la sua poetica, il proprio percorso, le fonti di ispirazione che nutrono il suo immaginario e il ruolo della pittura nella società contemporanea. L’esposizione sarà visitabile fino al 1 maggio 2022.

Caterina Fondelli: Vorrei iniziare quest’intervista con una riflessione sul particolare luogo in cui ci troviamo. Ogni volta che mi è capitato di visitare il Museo Stefano Bardini, mi è sovvenuto alla mente un paragone basato sulla similarità del contesto e della figura di collezionista molto vicina a quella di Sir John Soane e della sua casa-museo di Londra.

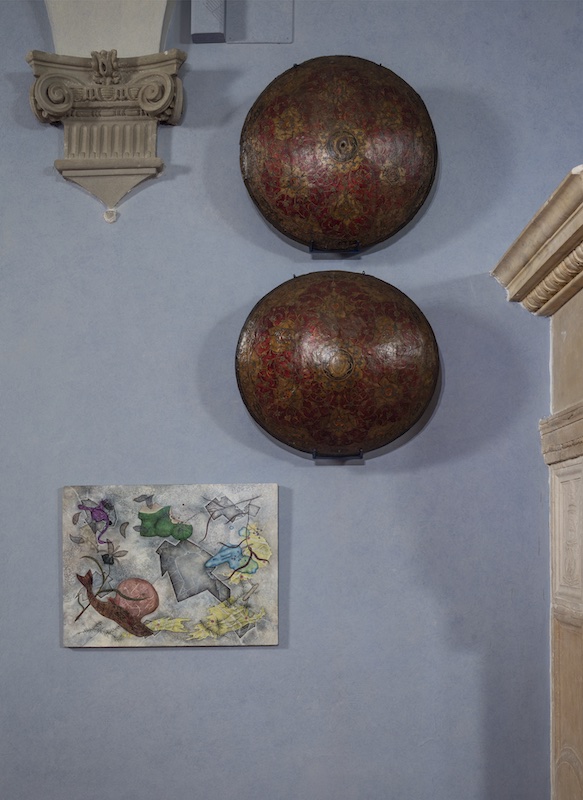

Sebbene ci siano molte connessioni fra i due personaggi, sicuramente gli spazi qui di Firenze sono differenti, così come l’atmosfera stessa e anche il tipo di dialogo che un artista possa crearvi. Quello che vorrei chiederti è: che cosa significa per te essere qui al Museo Stefano Bardini oggi e aver avuto la possibilità di stabilire una conversazione fra la tua arte e la collezione qui custodita che va indietro fino al XVIII secolo? Immagino sia stata una sfida. Ti ha regalato possibilità di sperimentare questa mostra? Siamo in uno spazio unico nel suo genere, una sorta di Wunderkammer, un ambiente quindi specifico e non l’usuale “white cube”.

Anj Smith: Sono davvero molto grata per l’apertura di visione che la città di Firenze, che mi ha invitata, dimostra e nello specifico il Museo Stefano Bardini. Il modo in cui la Storia e la sua eredità vengono custodite è commovente. Nel museo si possono trovare piccoli frammenti ovunque, ogni cosa è apprezzata e considerata.

Sono un’artista contemporanea, ma sono anche un’artista che crede di dover tenere di conto del nostro contesto storico, non curandosi di quanto difficile e problematica la Storia dell’Arte sia per noi nel 2022; dobbiamo comunque interrogarla e capirla per poter navigare verso il futuro. Credo fermamente nell’affrontare la Storia dell’Arte e questo informa la mia pratica, quindi effettivamente lavorare qui a Firenze e potervi contestualizzare la mia arte è un’esperienza molto profonda per me, anche se questo tipo di processi non sono mai semplici ed immediati, ho trovato moltissimi spunti di ispirazione ovviamente. Ogni volta che torno a Firenze è così: più imparo e più mi sembra di non conoscere niente. Sono affascinata anche dalla letteratura italiana, come Boccaccio, ho un’ossessione per il Decameron..

C.F.: Ho letto infatti nel web a riguardo e del fatto che vorresti tanto poterlo leggere in italiano.

A.S.: Sì, è vero e sto proprio studiando italiano al momento!

C.F.: Ho anche ascoltato tue interviste precedenti in cui sottolineavi la fondamentale connessione fra linguaggio ed arte, come le sfumature e i pensieri trasmessi con le parole si possano rispecchiare nella pratica artistica. Provenendo da un background ibrido, in cui ho avuto modo di studiare le lingue straniere unite alla storia dell’arte, credo fermamente in questo tipo di legami, che talvolta risultano sottovalutati e non utilizzati da tutti gli artisti.

A.S.: Sono veramente molto interessata a queste connessioni, visto che pratico la sinestesia ed ho sempre prestato attenzione a queste trasmissioni sinaptiche.

C.F.: Parlando della tua pratica e del processo di creazione, spesso descrivi il ruolo essenziale del tempo nella tua pittura, ad esempio alcune tue opere hanno richiesto anni per arrivare ad un compimento. Dal punto di vista del fruitore, nell’interazione con la tua arte, evidenzi l’importanza di prendersi del tempo per contemplare l’opera, in modo da donarle la giusta attenzione. La nostra relazione con il concetto di tempo è completamente cambiata a causa della pandemia, che stiamo ancora affrontando. Ritieni che il nostro legame con l’arte sia stato condizionato da questo approccio rivoluzionato? E, in tal caso, lo consideri un nuovo e positivo cammino da seguire?

A.S.: Penso che il tempo rivelerà se si tratti o meno di una cosa a lungo termine, ma credo anche che siamo così abituati a vivere nel modo in cui la nostra società è organizzata. Tutto è una merce. Siamo assuefatti ad un certo ritmo di consumo, che si tratti di un prodotto, come del modo in cui sperimentiamo l’arte; è perciò davvero controcultura dire che impiego più di un decennio a realizzare un dipinto. Ovviamente non è una cosa comune, di solito ho bisogno di alcuni mesi per eseguire un’opera, però effettivamente questo tipo di cose richiedono del tempo. Se si vuole costruire un certo strato di luminosità, si può benissimo ottenere un rosso intenso in un’ora, ma per raggiungere una stratificazione fatta di trasparenze ci vuole tempo e quello che risulta alla fine è come un gioiello.

C’è qualcosa di assolutamente radicale in questo e ora siamo stati costretti a rallentare a causa della pandemia. Sarebbe importante poter dilatare questa attitudine sul lungo termine, non solo per poter contemplare un dipinto e farne emergere i dettagli, ma soprattutto per far in modo di sviluppare delle facoltà critiche, che hanno numerose ricadute sociali.

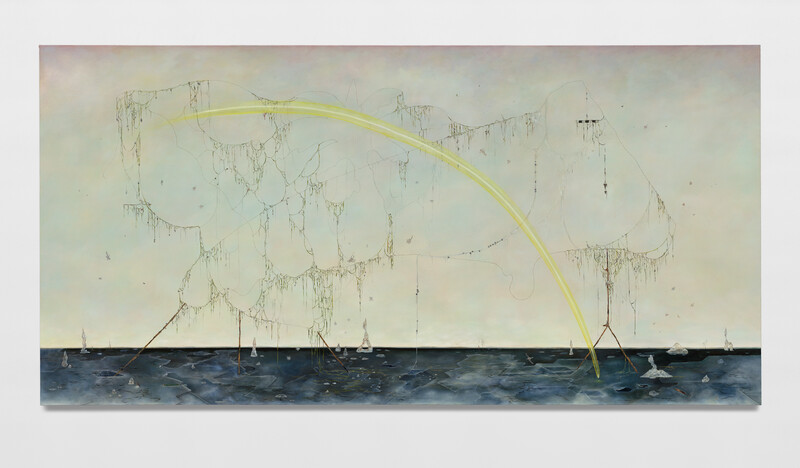

Come linguista, potrai apprezzare il grande dipinto al secondo piano intitolato Source, Sender, Channel, Message. Molte cose accadono in esso, non si tratta soltanto della situazione a livello ecologico in cui ci troviamo e della preoccupazione per il cambiamento climatico; è sicuramente un dipinto dei nostri tempi, ma si apre anche su un ulteriore livello di ansia esistenziale.

Source, Sender, Channel, Message

2020-21 Oil on linen 150 x 301 x 4 cm / 59 x 118 1/2 x 1 5/8 inches

© AnjSmith Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Copyright Photography©2021 Alex Delfanne, All Rights Reserved.

Talvolta il linguaggio risulta molto permeabile e non riusciamo a captare l’esperienza di qualcosa completamente, questo risulta davvero molto alienante. Questo è il tema che il quadro affronta: ci parla di tentativi di comunicazione che hanno fallito o non sono stati ricevuti, molto simile a come funziona il linguaggio. Per molto tempo ho studiato le teorie di Noam Chomsky e l’idea che il linguaggio sia l’unico strumento di comunicazione che abbiamo come esseri umani, l’unico modo di poter incapsulare quindi la nostra esperienza. Nasce perciò un grande interrogativo: come è possibile una reale comunicazione? Questi dilemmi sono stati costantemente presenti nella mia mente mentre dipingevo quell’opera.

Mi è stato necessario molto tempo per dare il giusto valore al tentativo stesso di comunicazione, che è valido in sé, anche quando è fallimentare. Il titolo del dipinto Names of the Hare fa riferimento alla straordinaria poesia scritta nel XIII secolo in Inghilterra e tradotta dal grande scrittore irlandese Seamus Heaney dal Middle English. Essa cita i 77 nomi con cui chiamare una lepre ed è una specie di incantesimo, il contadino cerca l’animale ripetendo questa litania e l’intenzione finale è appunto quella di catturarlo.

Names of the Hare

2017-18 Oil on linen 65.5 x 50 cm / 25 3/4 x 19 5/8 inches

© AnjSmith Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Copyright Photography©2018 Alex Delfanne, All Rights Reserved.

Per me questo componimento rappresenta realmente che cosa significhi dipingere adesso: è come se tu stessi cercando di incapsulare tramite l’uso del linguaggio visivo, utilizzando quindi lo stesso principio per catturare qualcosa che sta scappando e ciò che rimane è la traccia di questo tentativo di cattura. Ancora una volta, stiamo parlando di godersi il percorso, il processo e dare valore alle cose che vengono trascurate o a malapena notate: questa è una componente enorme nella mia pratica.

C.F.: Ho inoltre sentito che Domenico Gnoli con la sua attenzione per il dettaglio, i suoi motivi, i tessuti e così via, è stato di grande ispirazione per te. A Milano è stata di recente ospitata una stupenda retrospettiva sull’artista, l’ho quindi trovata una fortunata coincidenza. Volevo domandarti, qual è stato il ruolo dell’arte di Gnoli in generale nella tua poetica e nello specifico nella selezione di dipinti qui al Bardini?

A.S.: Domenico Gnoli aveva una visione del tutto singolare ed è stato toccante vedere come le persone in occasione della mostra, lo apprezzassero e lo capissero. Sono interessata nel fare qualcosa che sia focalizzato sulla mia esperienza e che nessun altro abbia mai fatto prima. Ci sono inoltre tante ossessioni sovrapposte fra le sue e le mie: la moda, su tutto. Lui era estremamente intelligente! Talvolta la moda viene infatti liquidata come frivola, in una prospettiva piuttosto misogina. In realtà la moda è un linguaggio importante quanto gli altri, questa è una delle molte ragioni per cui amo l’Italia! Gnoli parlava totalmente di moda e lo trovo qualcosa di veramente affascinante.

Ho sempre ritenuto che i vestiti incorporino lo Zeitgeist e i suoi dipinti sono talmente carichi a livello psicologico. Egli possedeva un punto di vista unico e una maniera peculiare di ritrarre il corpo. Sono effettivamente dei dipinti “difficili”, se ci si avvicina si nota la presenza della sabbia! Non mi sarei mai aspettata di viverli nel modo in cui ho fatto durante la mostra. Così epocale.

C.F.: Sono così materici, molto più di quanto sia comprensibile tramite i libri o le riproduzioni fotografiche.

A.S.: Non si possono fotografare i miei dipinti e così accade con i suoi. Ci deve essere una certa qualità nella pittura che sfugge alla digitalizzazione. Amo il fatto che questi dipinti siano “difficili”, visto che abbiamo proprio parlato di rapido consumo.

C.F.: Ho altresì riscontrato una similarità fra il modo in cui tu e Gnoli rappresentate gli animali, il bestiario e i pattern ad essi connessi.

A.S.: Oh sì, questo è molto interessante. Credo sia un aspetto psicologico, egli non aveva timore di addentrarsi nel terreno psicologico, che può essere oscuro e riguarda l’interiorità. Egli adopera una tecnica di ingrandimento su una specifica area dei capi di vestiario ed in tal modo l’interiorità si rivela a poco a poco, insieme alla solitudine, al senso di isolamento e lo ottiene con un’operazione di tipo feticista, andando cioè a zoomare sui dettagli.

C.F.: Abbiamo menzionato questo elemento psicologico presente nella pittura. Tu fai infatti spesso luce su importanti argomenti, sia da un punto di vista individuale che sociale, come l’inquietudine e la salute mentale. Potresti spiegare perché ti concentri su questi aspetti e come lo metti in atto attraverso la tua arte?

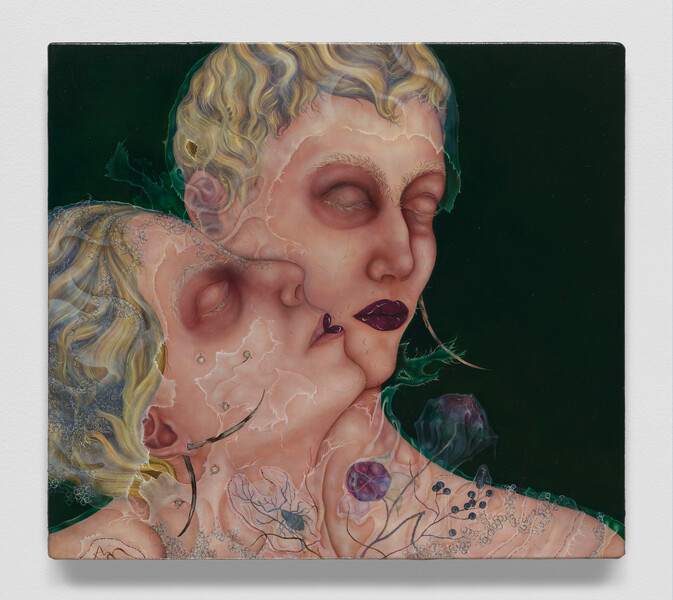

A.S.: Faccio ricorso alla mia esperienza di vita, se percepisco che essa abbia una risonanza sociale. Non è solamente qualcosa di illustrativo su ciò che ho vissuto, ma lo trovo come un’auto-indulgenza, visto che penso che gli artisti ricoprano una funzione sociale. Per esempio, nell’opera The Lover, il dipinto che proviene dal periodo della psicosi, ne ho parlato perché trovavo avesse un riscontro contemporaneo, al di fuori della mia esperienza personale. Con la pandemia, molte persone hanno avuto a che fare con la catastrofizzazione o il rimuginare, cose familiari a coloro che hanno affrontato periodi di crisi a livello psicologico. Tutto ciò fa parte di una conversazione in cui tutti, su vari livelli, possiamo ritrovarci coinvolti.

The Lover

2020 Oil on linen 38.7 x 43.1 cm / 15 1/4 x 17 inches

© AnjSmith Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Copyright Photography©2020 Alex Delfanne, All Rights Reserved

C.F.: Come ultimo quesito, ma non per questo meno importante, una grande domanda. Potendo includerti fra i più importanti esponenti della pittura contemporanea e potendo considerarti specialmente una pensatrice, qual è il tuo pensiero in merito alla pittura nel 2022 e oltre?

A.S.: Penso che un nuovo vento, un’aria fresca, stia soffiando sulla pittura contemporanea al momento. La pittura trova sempre il modo di risorgere e le possibilità sono illimitate.

Dobbiamo stare attenti però a non proiettare sulle nuove voci che invitiamo (ad unirsi al canone) uno sguardo rigido e antiquato. Le persone dovrebbero ascoltare, piuttosto che insistere su metodi passati di interpretazione. Il dialogo riuscirebbe in questo modo a sbocciare in qualcosa di incredibile. Anche alla mia poetica vengono attribuiti molti riferimenti come “Oh sembra molto “Surreale”, legata al movimento surrealista” e così via, il che non è necessariamente vero. È un approccio meno letterale, maggiormente obliquo e che abbraccia la complessità e le incertezze del nostro tempo.

ANJ SMITH | A Willow Grows Aslant the Brook

a cura di Sergio Risaliti

17 dicembre 2021 – 1 maggio 2022

Museo Stefano Bardini

Via dei Renai, 37 – Firenze

In conversation with Anj Smith: a profound dialogue on contemporary painting

On the occasion of the solo exhibition “Anj Smith. A Willow Grows Aslant The Brook” dedicated to the artist Anj Smith and curated by Sergio Risaliti at Museo Stefano Bardini in Florence, the contemporary painter recounts her poetics, the paths and sources of inspiration that enhanced her imagery and the role of painting in contemporary society. The show will be on view until May 1, 2022.

Caterina Fondelli: I would like to start this interview with a reflection upon the place we are in. Every time I visit the Bardini it comes to my mind a comparison to a similar context and collector figure as the one of Sir John Soane and his house-museum in London. Although there are many connections between the two, of course the space here in Florence is different, the atmosphere too, and also the dialogue an artist can create. What I would like to ask you is: what does it mean to you to be here at the Museo Stefano Bardini today, to have the chance to create a dialogue between your art and a collection that goes back to the 18th century? Was it challenging? What possibilities to experiment did this exhibition give you? We are in a peculiar place, a kind of little Wunderkammer, a specific environment and not a usual white cube.

Anj Smith: I am so grateful for the open attitude with which the city of Florence welcomed me, specifically the Museo Stefano Bardini. The way that history and historical legacy is taken care of here is very touching. At the Bardini you can see little fragments everywhere. Everything is treasured and considered.

I am of course a contemporary artist, but I am an artist that believes we have to take into account our historical context . No matter how difficult or problematic art ‘history’ is to us now in 2022, we have to interrogate that and understand where we come from in order for us to navigate forward. I do really believe in tackling art ‘history’ and that informs my practice, so to actually work in Florence and contextualize my work here is a very profound experience for me. However, these things are never just cut-and-dried. I find so much that inspires me. Every time I come to Florence, it feels like the more I learn, the more I know nothing. I am fascinated by Italian writing as well, I love Boccaccio, I have an obsession with the Decameron..

C.F.: I have read something on the web about you would love to read it in Italian.

A.S.: Yes, it is true and I am actually learning Italian!

C.F.: I have also heard a past interview of yours where you underline the pivotal connection among language and art, how the nuances and reflections in words can be mirrored in art. I have a hybrid background, I studied foreign languages blended with arts, and in my opinion these ties are really at times underrated and not used by all artists.

A.S.: I am truly interested in these connections. Because I have synesthesia, I have always been mindful of these synaptic transmissions.

C.F.: Talking about your practice and creation procedure, you often describe the essential role of time in your painting, some pieces take you years to be completed. From the viewer’s point of view, in interacting with your art, you also stress the importance of taking some time for contemplation in front of the work, in order to pay the proper attention to it. Our relationship with time has completely changed due to the pandemic period we are still experiencing. Do you think that our connection with art was affected too by this revolutionized approach? And, in that case, do you consider it a new and positive path to follow?

A.S.: I think time will tell if this is a long-term thing, but I also think we have become so used to living the way our society is organized. Everything is a commodity. We are used to a certain pace of consumption, whether that is a product or even how we experience art. It does feel really countercultural to say that it could take me over a decade to realize a painting. That is not usual, it usually takes me a few months to execute a painting, but actually these things take time. If you want to build up a layer of luminosity, you could just get a thick red and do that in an hour, but it takes time to get a sheer layer over a sheer layer. And then it is like a jewel.

There is something quite radical in that, and now we have been forced to slow down by the pandemic. I think is so important for this to be a long term thing, not just in terms of being able to observe a painting and let details emerge, but also in order to fully develop critical faculties. For this has social implications.

As a linguist you will appreciate the large painting upstairs titled Source, Sender, Channel, Message. There are many different things going on in it, it is not just about the situation we find ourselves regarding ecology or the concern about global warming. This painting is of our time and so an expression of this anxiety that we feel, but it also opens out to another layer – of existential anxiety.

Sometimes language seems so porous. In that you can never fully ‘capture’ experience through it, and this is quite an alienating thing to feel. This is what the painting tries to address and deal with – attempts to communicate that have failed or not been received – very much like how language functions. For so long, I have studied Noam Chomsky’s theories and the idea that language is the only tool we have as human beings to communicate. This is our only way to encapsulate experience, and so the great question is: how is true communication possible? That was always in my mind while I was painting that work.

And what took me a long time to really appreciate, is that the attempt at communication is valid in itself. Even if it fails. The title of my painting Names of the Hare refers to an amazing poem written in the 13th century in England and translated by the brilliant Irish writer Seamus Heaney from Middle English. It is 77 names for the hare and it is like an incantation – the farmer is trying to find the hare by repeating this litany of words. The final intention is the capture of the hare. For me this really represents what it means to be painting now. You are trying to encapsulate something using visual language, with the same principle of capturing something that escapes. It escapes but you have a trace left of the attempt of capture. Again, this is about enjoying the journey, the process and valuing things that are overlooked and barely there, that is a huge part of my practice.

C.F.: I have heard you said Domenica Gnoli, his attention to details, patterns, fabrics and so on, is truly inspiring to you. In Milan, there was lately an amazing Gnoli’s retrospective, so I have considered this a wonderful and lucky coincidence. So, what was the importance of Gnoli’s art in general to your art and specifically to the selections of paintings here at the Bardini?

A.S.: Gnoli was so unique in his vision and it was so heart-warming to see people understanding and appreciating it (at the exhibition). I am interested in making something from my experiences that has not already been made. There are also so many overlapping obsessions of his and of mine: fashion, for example. He was so smart! Sometimes fashion can be dismissed and considered frivolous, potentially from an internalized misogyny. Fashion is an important language like anything else, another reason why I love Italy! Gnoli totally spoke fashion, which I find so fascinating. I think that clothes encapsulate a zeitgeist and his paintings are so psychologically charged. He had a singularity in his vision and a peculiar way of portraying the body. They are actually quite difficult paintings. When you go up close there is the sand! I was not expecting to experience those paintings the way that I did. Very radical.

C.F.: They are so textured, more than you can see through books and pictures.

A.S.: You cannot photograph my paintings and you cannot photograph his paintings. There has to be a quality about painting that escapes digitalization. I love the fact that they are difficult paintings, as we have talked about easy consumption.

C.F.: And I also found a similarity with yours in the way he represented animals, bestiary and the patterns connected to them.

A.S.: Oh yes, interesting. I think it is so psychological, he is not afraid of going into psychological territory that is dark and about interiority. He zoomed in on a specific area of clothing that slowly reveals itself to address loneliness, isolation… And he did it in such a fetishistic manner, closing in on details.

C.F.: As we mentioned this psychological aspect of painting, you actually shed light on important subjects, both from an individual and social point of view, such as inquietude and also mental health. Could you explain a bit more why you focus on these aspects and how do you accomplish it through your paintings?

A.S.: I only have used my life experiences, if I feel they have a social resonance. It is not just ‘illustrative’ of an experience. I would consider that as self-indulgent and I believe artists have a social function. So, for example, with The Lover, the painting that came from a period of psychosis, I spoke about that because I actually feel it has a contemporary resonance outside of my own experience. With the pandemic, a lot of people encountered rumination, and catastrophization and other things familiar to those who have been through a mental health crisis. I believe it is part of a conversation that many people can relate to now, to some degree.

C.F.: Last but of course not least, a big question. As we should consider you one the most important contemporary painters and especially a thinker, what is your thought on painting in 2022 and beyond?

A.S.: I think there is a new and exciting wind blowing through contemporary painting right now. Painting always resurrects, and the possibilities are limitless.

What we ought to be careful of when inviting new voices (to join the canon) is to not project a fixed or old way of judging our work. People should listen rather than insist on these old ways of reading.Then the conversation will blossom out into something incredible. With my practice, for example, many people say “Oh it looks ‘surreal’, it is connected to the Surrealism movement” which is not necessarily true. It is just a less literal, more oblique approach that embraces complexities and uncertainties of our time.