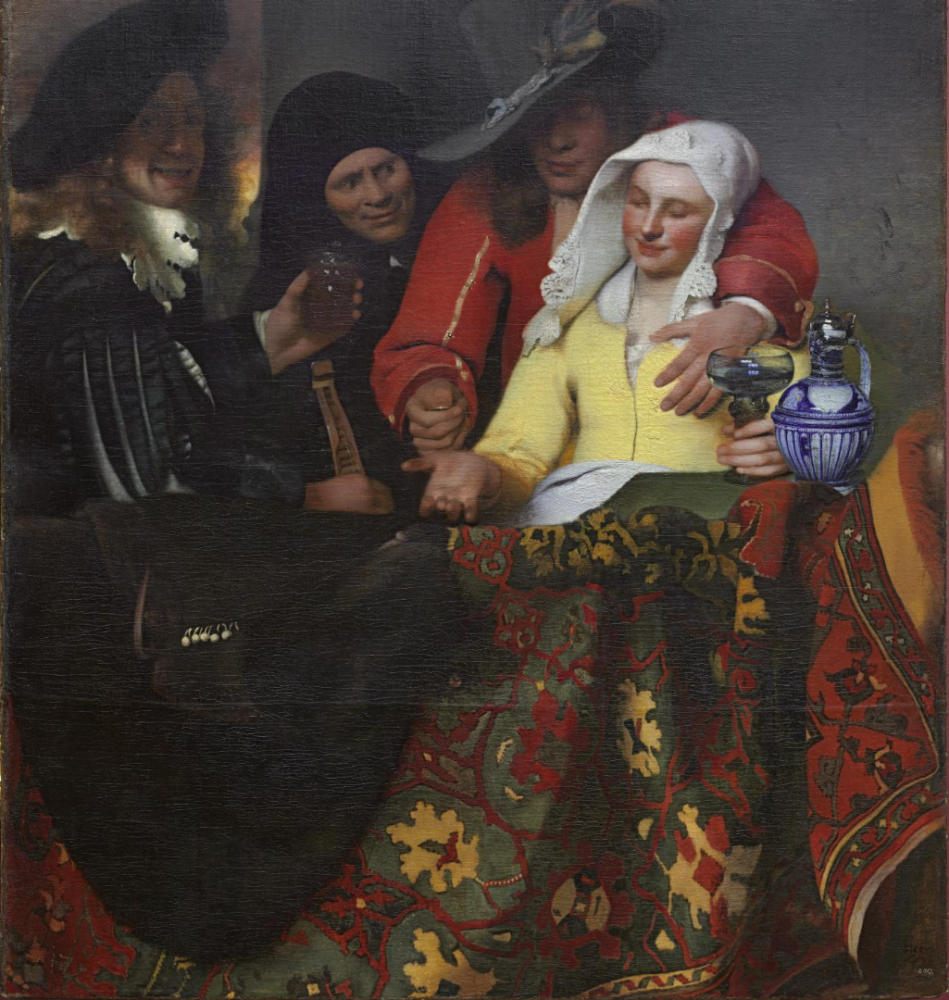

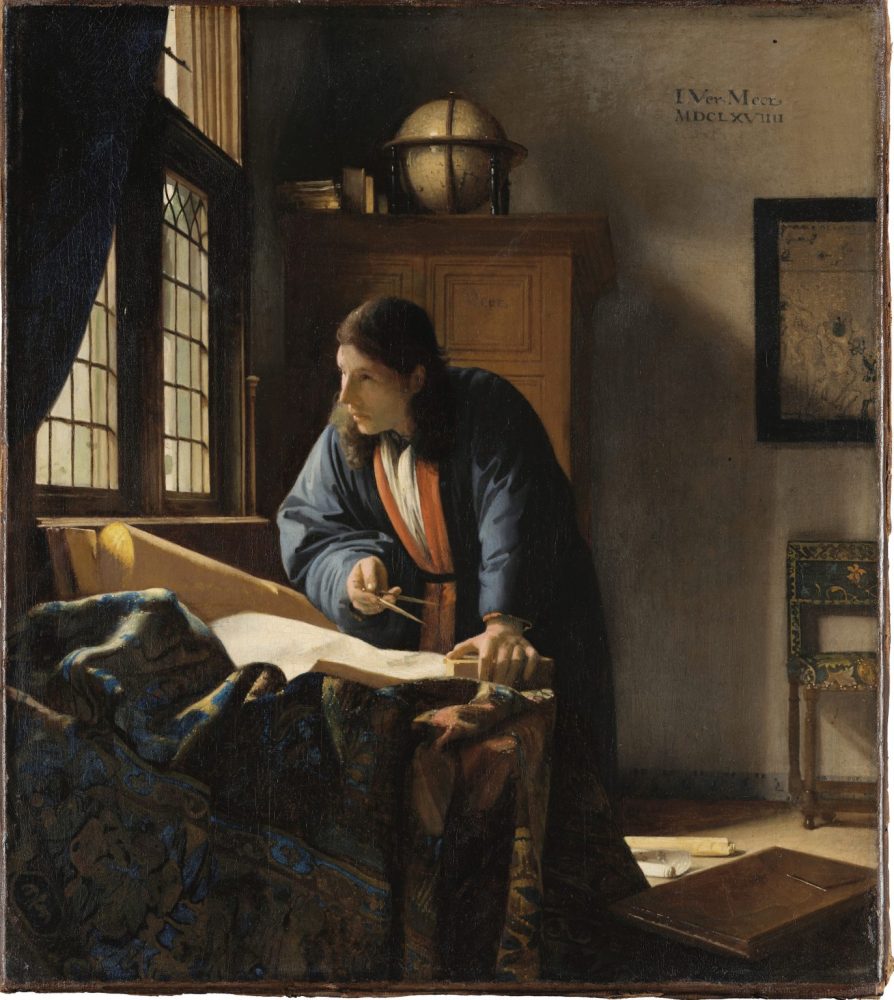

Al Rijksmuseum di Amsterdam è in mostra – dal 10 febbraio al 4 giugno 2023 – la più grande esposizione mai realizzata su Johannes Vermeer. 27 opere, sulle 37 realizzate dall’artista, compongono un evento mai visto e probabilmente irripetibile.

Blaise Pascal, nelle sue Lettere Provinciali, scrisse: “Se avessi avuto più tempo ti avrei scritto una lettera più breve“. Ovvero: per raggiungere l’essenza di ciò che vorrei dire non servono troppe parole; anzi, troppe parole annacquano il significato di quel che intendo trasmettere. Al contrario, poche ma precise parole possono racchiudere un mondo. Il riferimento, in sostanza, è al labor limae latino, alla sgrezzatura di un testo, di una storia, di un concetto. É la lunga ricerca della perfezione. Che per essere raggiunta richiede tempo. Blaise Pascal, a quanto pare, non ne ha avuto abbastanza. Johannes Vermeer, invece, si.

Johannes Vermeer ha avuto tempo, ma soprattutto non ha avuto la disperata necessità di vendere per vivere, di dipingere per vendere. O almeno non le sue opere: era mercante d’arte e presidente di alcuni gilde di artisti. Così, per quanto riguarda più strettamente la sua produzione, ha potuto concentrarsi su quel che prediligeva nel modo che prediligeva. Il risultato è un corpus di lavori piuttosto esiguo, con appena 37 tele giunte fino a noi. Ma preciso, cesellato, essenziale, unico. Del resto un grande artista non lo si misura per la quantità di opere prodotte, ma per l’universo – in questo caso visivo – che è riuscito a generare.

Il mondo che Vermeer delinea è quello in cui le occupazioni più ordinarie si trasformano in riti miracolosi. Qui la quiete, la vita quotidiana assumono un valore quasi ultraterreno. Per sfiorare l’eterno, per cristallizzare la poesia che lo animava, non ha guardato a grandi scene bibliche o mitologiche, non si è affidato a committenti illustri o celebri soggetti. Al contrario, aveva compreso che spesso il valore più potente risiede nelle piccole cose. Umili nel contenuto, ma anche ridotte per quantità. Per raccontarci la sua arte non ha avuto bisogno di molte opere, e nemmeno di grandi temi ed epiche imprese. Insomma: Less is more. Vermeer ha avuto il tempo di scriverci una lettera brevissima.

E ancora: nei suoi dipinti spesso c’è solo un soggetto, forse due, raramente tre. Quasi sempre è femminile. La ragazza è raffigurata all’interno di una stanza, protetta nella sua intimità, intenta a compiere azioni quotidiane come preparare il pranzo, cucire, suonare. Oppure, e qui il pensiero torna di nuovo a Pascal, leggere o scrivere una lettera. La lettera è lo strumento per eccellenza con cui l’esterno penetra all’interno, il mezzo per cui due mondi si incontrano o una storia inizia. Nella loro semplicità, le scene ideate da Vermeer paiono malinconici ed efficaci meccanismi narrativi: la vita di una donna isolata tra quattro mura viene agitata da un messaggio improvviso, che arriva dall’esterno ad agitare la sua vita come il fascio di luce, che proviene quasi sempre da sinistra, illumina la scena.

Tale sentimento è incrementato dall’allestimento scenico del dipinto, in cui Vermeer dissemina indizi più o meno espliciti del fatto che i suoi personaggi siano stati interrotti. Nel mezzo di un’azione, di una lettura, di una riflessione. Come se l’artista volesse rappresentare l’esatto momento in cui la loro esistenza ha iniziato a cambiare. Ma in fondo, forse, è troppo. Nella poetica della riduzione adottata da Vermeer sarebbe più opportuno pensare che a cambiare sarà solo la loro giornata. Magari nemmeno quella. Ma è proprio la sensazione di stare assistendo a un momento potenzialmente cruciale delle loro vite a rendere queste scene così potenti.

E poi, ovviamente, c’è la resa tecnica, la luce, le tende, i muri, gli affreschi, le mappe, gli abiti, i gioielli, i riflessi, le brocche, i cappelli, le sedie, le tovaglie, le coperte, i pavimenti, i tavoli, le piastrelle. Tutta gli elementi che compongono quella vita che ci scorre davanti mentre pensiamo ad altro. Vermeer la prende e la immortala sulla tela, suggerendoci che l’essenza dell’esistenza non è poi così inafferrabile come crediamo.

Un aspetto, questo, che affascinò anche Marcel Proust. Che di vita, tempo ed esistenza se ne intendeva. In particolare, lo scrittore francese considera la Veduta di Delft il “quadro più bello del mondo“. Tanto da inscenare l’episodio della morte di Bergotte, personaggio della Recherche, proprio davanti al quadro. Bergotte ha un malore che pensa sia provocato da patate poco cotte, e prima di morire le ultime riflessioni sono sui suoi libri: “I miei ultimi libri sono troppo secchi, avrei dovuto stendere più strati di colore, rendere la mia frase preziosa in sé, come quel piccolo lembo di muro giallo“. Avrebbe voluto, insomma, avere più tempo per dare il giusto spessore alla sua opera. E ancora Bergotte, mentre sta per morire, si ripete: “Piccolo lembo di muro giallo con tettoia, piccolo lembo di muro giallo“, riferendosi a un dettaglio, forse marginale, ma per lui potente, della Veduta di Delft. Come se in punto di morte avesse capito che il segreto della vita, come dell’arte, sta nell’ordinario. E che come nell’arte, anche nella vita, l’uomo può trovare se stesso solo nei luoghi dove nessuno, oltre a lui, avrebbe mai pensato di guardare.

Avventurarsi in città

Prime ambizioni

I primi interni

Guardando fuori

Da vicino

Richiamo musicale

Lettere dal mondo esterno

Gentiluomini

Visione del mondo

Riflessioni su vanità e fede