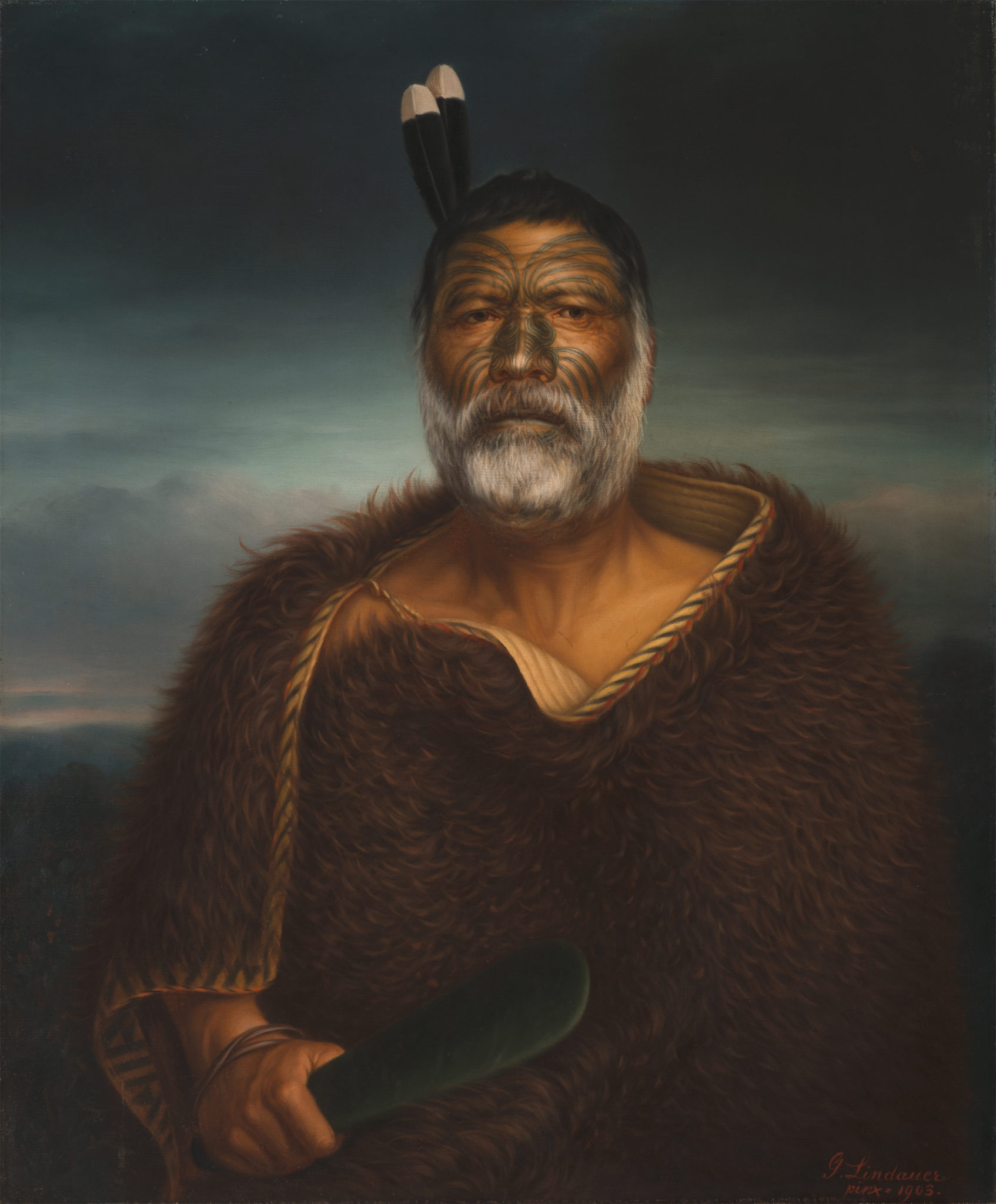

Paora Tuhaere, 1895

67.7 x 56.3 cm, oil on canvas

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of H. E. Partridge, 1915

Recently I have visited a very particular exhibition of the Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, in collaboration with Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, “Gottfried Lindauer. The Māori Portraits” in Berlin. Indeed it is a very particular event – as it is the first time that the descendants of the personalities depicted have, together with Haerewa (Māori scholars and artists acting as consultants to Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki), given permission for the pictures to be shown outside of Aotearoa/New Zealand. The pictures have never left New Zealand because, for the descendants of the personalities depicted, the memory of their ancestors is part of living and the former are always mindful of the bonds tying successive generations to their lineage, history and identity right up to today.

Mrs Paramena, ca. 1885

85.2 x 67.5 cm, oil on canvas

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, purchased 1995 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds

Gottfried Lindauer, born in 1839 in Pilsen (today in the Czech Republic), is one of the few painters of the late 19th century to devote himself in his work almost exclusively to depicting an indigenous people, the Māori of Aotearoa/New Zealand, in portraits and genre paintings. Gottfried Lindauer was trained at the Vienna Academy of Art. His teachers were Leopold Kuppelwieser, Josef von Führich and Carl Hemerlein. As the increasing popularity of photography began to jeopardise his chances of commissions in Pilsen, Lindauer decided to emigrate by taking ship from Hamburg.

Kuinioroa, daughter of Rangi Kopinga – Te Rangi Pikinga, no date

61.4 x 51.4 cm, oil on canvas

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of H. E. Partridge, 1915

He arrived in Wellington harbour in 1874, settled in the merchant city of Auckland, where he met his patron, the businessman, Henry Partridge, who wanted to record the Māori culture.

Paora Tuhaere, 1895

67.7 x 56.3 cm, oil on canvas

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of H. E. Partridge, 1915

The exhibition opens up a further chapter in the history of 19th century art and one focusing on the complex web of relationships already woven around the whole world. With its premier collection from the 19th century, the Alte Nationalgalerie forms an ideal context for this exhibition. The bitterly conducted struggle at the end of the 19th century over acquisitions of the French art of Impressionism does, in fact, define the decisive background to the history of collecting and to the identity of the Nationalgalerie. Previously, the museum’s international perspective surveyed a European history of art and excluded the context of what was already a globalised world in the 19th century.

Mr Paramena, ca. 1885

85 x 67.5 cm, oil on canvas

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, purchased 1995 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds

The questions of inclusion and exclusion, as developed in the context of contemporary art with the aim of scrutinising our own cultural practice, are highly relevant here, as the portraits of tattooed Māori bear witness to a genuine and rare bicultural interaction and demonstrate the energy arising from the encounter between very different people, societies and cultures.

So, if you happen to be in Berlin, try to visit this fantastic exposition, that for me was like a travelling in the past.